By Aaron Person

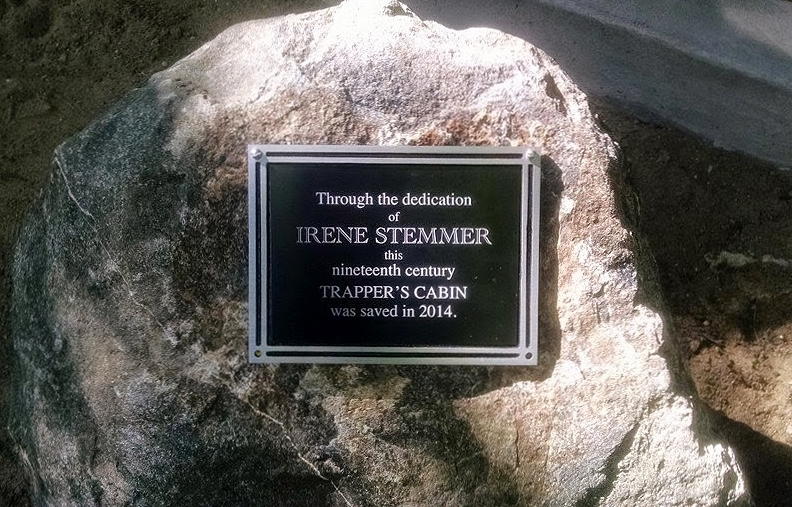

Strolling through the woods of Shaver Park in Wayzata, visitors and local residents alike are bound to pass by a little log cabin that has seemingly appeared out of nowhere. If they read the plaque standing next to the structure, passersby might be shocked to discover that this unsuspecting shack is actually the oldest surviving structure in Wayzata and likely the oldest in the greater Lake Minnetonka area, possibly dating back to the 1850s. But it didn’t simply appear there spontaneously. Bolted to a boulder near the cabin’s entrance is another plaque that reads: “Through the dedication of Irene Stemmer this nineteenth century Trapper’s Cabin was saved in 2014.”

The “Trapper’s Cabin,” as it is called, was originally located east of town, just north of the railroad tracks off Bushaway Road, though the tracks probably didn’t even exist when the cabin was built. Although it is unknown who actually built the cabin, records show that Horace Norton was the original owner of the property it sat on. Norton purchased the land in 1855 from the federal government under the Act of Preemption. However, this does not necessarily mean that Norton built the cabin – property owners of the time often bought land without actually visiting it, and it was common for squatters to build small, primitive shacks on the land without any official record. One theory, although purely based upon lore, suggests that the cabin was built by a Black logger who was sent out from Saint Paul to clear the land. Another theory suggests that it was built by an early trapper, which is why the structure has been referred to as the “Trapper’s Cabin” since the early 1900s. One thing that is certain, however, is that the cabin was constructed out of timber from nearby tamarack swamps, almost all of which were depleted early on for use as railroad ties and other construction. Tests conducted by the Department of Forest Resources at the University of Minnesota have confirmed this hypothesis.

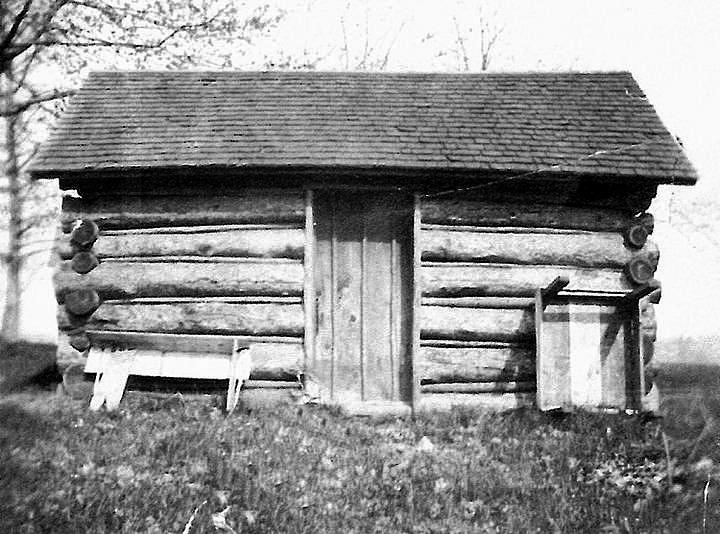

The earliest known photograph of the Trapper’s Cabin dates from 1889, when Thomas F. Andrews built the first real homestead on the property. Twice over the subsequent decades the site of the original Andrews residence was replaced by new homes, but the Trapper’s Cabin remained standing. By the middle of the Twentieth Century it appears that the cabin could have been used as a shed or as a playhouse by children in the neighborhood, though someone could have actually been living in it as late as 1937.

In recent years plans were presented to clear the property to make way for a new housing development. Work was to begin in 2012. This is when Irene Stemmer, Chairwoman of the Wayzata Heritage Preservation Board, stepped in by persuading the developer to donate the Trapper’s Cabin to the City. She hoped that the City could restore the building and place it on public land one day. However, the City Council was not initially convinced that the cabin was worth preserving due to the fact that its history was greatly unknown. Stemmer argued that it was worth preserving, asserting that it represented the lives of the people who made Wayzata and that it would be a reminder of the very first houses that appeared in the area. “If we don’t save it now,” she said, “we may never get another chance to honor our founder Oscar Garrison, our early settlers who hung in through grasshoppers, bad weather, and financial collapse. There’s no famous architect, but these were our real historic heroes who did indeed live in these humble abodes.” With that point made, the City Council was convinced.

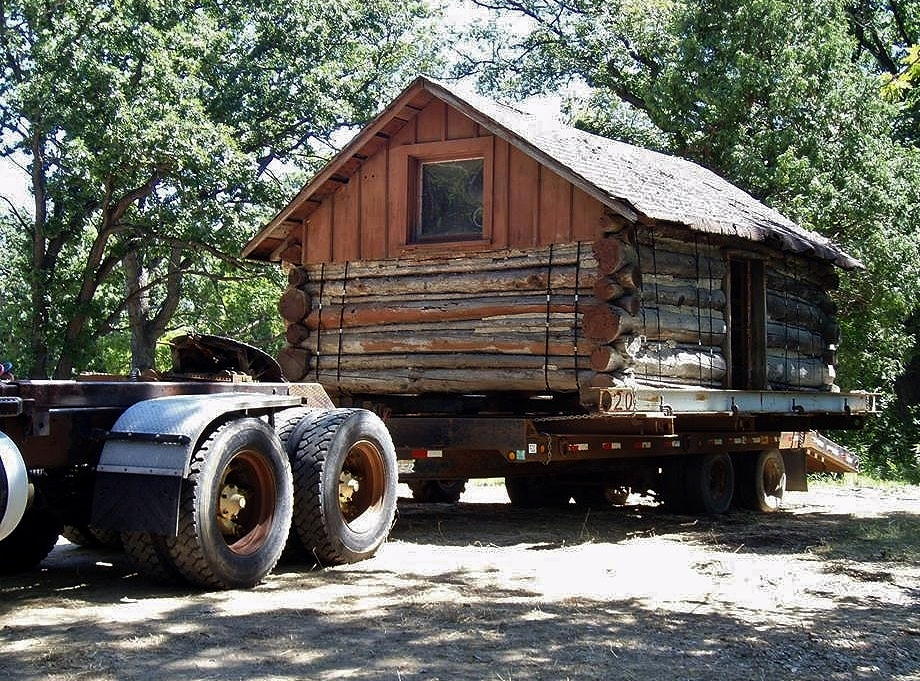

Presbyterian Homes and Services, the development firm behind the Promenade of Wayzata, was contracted to help move the cabin in 2013. They even agreed to pay for the move and for the cabin’s restoration. That summer the cabin was moved to the Public Works grounds on the other side of town. It was done in the middle of night to minimize traffic disruptions. “When I saw it standing on its [moving] pilings,” said Stemmer in a Star Tribune interview, “it was like The Little Engine That Could.“

Restoration slowly but surely ensued and was completed this past summer. In August a new concrete palette was poured in Shaver Park. This is where the cabin would be placed early on the morning of September 5. “To watch Larry Stubbs come off of Ferndale with that big Mack truck and back that trailer in between the trees and set it down on the middle of that cement slab, it was totally remarkable,” Stemmer said to a crowd of about forty people at the dedication ceremony the next day. “It is not easy to move a historic building from its original site, but when we need to, it can be done.”

Wayzata mayor Ken Willcox also spoke at the ceremony. “I call her Ms. Wayzata History,” he said. “She was the one to first recognize the historical significance of [this cabin] and took it on as her mission to preserve it for all time.”

“I couldn’t give it up because I knew we needed to have this cabin,” Stemmer said. “And now that it’s here, aren’t you glad we did this?”

At the end of the ceremony Mayor Willcox held up a small plaque and announced, “Before everyone leaves, I’d like to say thank you once again to all of you who contributed to making this project possible. But out of everyone who helped, there is only one person here that was behind it every step of the way. It wouldn’t have happened without her persistence, her tenacity, and her vision. So I’d like to present her with this plaque. It says ‘Through the dedication of Irene Stemmer this nineteenth century Trapper’s Cabin was saved in 2014.'”

Holding back tears with her hands across her chest, Stemmer replied with only two words: “It’s beautiful.”Stemmer and the Wayzata Heritage Preservation Board hope that the Trapper’s Cabin can be used as an interpretive space in the future. Indeed, educational programs have already been held within its confines. With the future of the structure now secure, it will certainly continue to be a reminder of Wayzata’s earliest days of settlement for generations to come.

(Editor’s note: Irene Stemmer will be officially retiring from the Wayzata Heritage Preservation Board on December 31, 2014.)