By Aaron Person

One of the most common questions that Minnehaha’s passengers like to ask is if there are plans to raise any of the other streetcar boats from the bottom of Lake Minnetonka. The simple answer is “no.” There are many reasons for this; aside from the logistical and economic obstacles that would have to be overcome, it is also illegal. According to the nonprofit Maritime Heritage Minnesota, shipwrecks at the bottom of any lake in Minnesota are subject to several laws at both the state and federal levels, including the Minnesota Field Archaeology Act (1963), the Minnesota Historic Sites Act (1965), and the Federal Abandoned Shipwrecks Act (1987), among others. These laws prevent shipwrecks from being looted or otherwise disturbed, let alone raised. They were enacted, in part, because submerged resources risk being damaged or destroyed if they are raised without proper care.

Many would be surprised to learn that Minnehaha was indeed raised illegally in 1980. So, how was it allowed to happen? The situation was rather complicated.

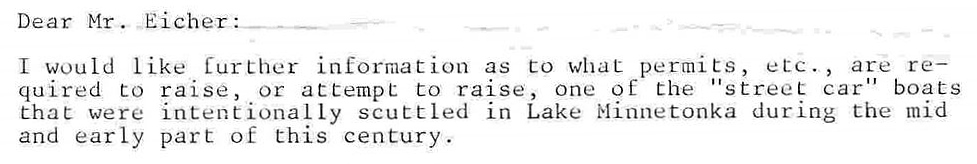

It began on August 21, 1979, when Fred Pearce sent a letter to the Minnesota Department of Administration. In the letter, Pearce expressed interest in raising one of the streetcar boats from the bottom of Lake Minnetonka. He further proposed converting it into a “dryland lounge” for his Mai Tai restaurant in Excelsior. For reasons unknown, it was thought that the boat in question was the Hopkins, one of Minnehaha‘s sister boats. Unlike the Como, Minnehaha, and White Bear, which were scuttled in 1926, the Hopkins was sold to a private entity, renamed Minnetonka, and used as an excursion boat for many years. It wasn’t scuttled until 1949.

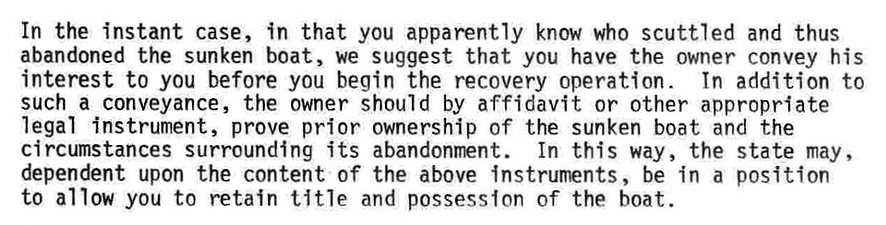

The Minnesota Department of Administration responded to Mr. Pearce on November 27, 1979. In this letter, the State listed all of the requirements needed for Mr. Pearce to obtain a salvage permit. The list of requirements was drawn after consulting with “several state agencies and the staff of the Attorney General” about the proposal. The State further recommended that Mr. Pearce have the last owner of the vessel prove prior ownership so that the State could “allow [Mr. Pearce] to retain title and possession of the boat.” Since the Minnetonka had been scuttled in 1949, it had not yet reached the 50-year threshold typically required to be considered a historic resource.

On January 25, 1980, ownership of the scuttled Minnetonka (the former Hopkins) was transferred to Fred Pearce. During this time, Mr. Pearce had been in communication with Jerry Provost, the diver who would lead the salvage effort. Mr. Provost had originally discovered the wreck lying in about 60 feet of water in July 1979. He began planning the salvage operation and hoped to do it in the summer of 1980.

The salvage operation officially began on August 25, 1980. Leading members of the team included Jerry Provost, Steve Anderson, Greg Hegi, and Bill Niccum. With the assistance of about 20 divers, three barges, three cranes, and eight airbags, the wreck finally emerged from the depths on August 29. However, it was not the wreck that everyone thought it was…

Once the wreck had been towed to mainland and hauled out of the water, its hull was cleaned and began to dry out. At that moment, the name “Minnehaha” appeared in four locations on the hull – it was not the Minnetonka after all.

Since Minnehaha had been scuttled in 1926, four years beyond the 50-year threshold for historic properties, it was legally considered a historic resource and thus subject to the Minnesota Field Archaeology Act and the Minnesota Historic Sites Act. Furthermore, since the vessel was not the Minnetonka, Fred Pearce could not claim any legal ownership – it was State property. This meant that the vessel had been raised illegally.

Had the State known that the wreck in question was the Minnehaha, the Department of Administration probably would not have allowed it to be raised. Thus, with the act already done, the State found itself in an awkward position. Since the Twin City Rapid Transit Company had been the last owner of the vessel, it was offered to Metro Transit (TCRT’s immediate successor). However, Metro Transit expressed zero interest in the vessel. Discussions about re-scuttling the boat were floated around but ended with no action because such an act would violate Minnesota Pollution Control Agency policies.

Meanwhile, the vessel sat in limbo at Bill Niccum’s property in Shorewood. In 1984, after four years of being exposed to the elements, ownership was transferred to a nonprofit organization called the Inland Marine Interpretive Center which had been formed by Darel and LaVerna Leipold. The Leipolds’ goal was to restore the vessel to operating condition, but fundraising struggles prevented this from happening.

Discussions started by Leo Meloche in 1989 eventually led to ownership being transferred to the Minnesota Transportation Museum in 1990. The Minnehaha Restoration Project finally began later that year and officially wrapped up on May 25, 1996, when Minnehaha re-entered passenger service for the first time in 70 years. The project took at least $500,000 and 85,000 volunteer manhours to complete. Due to deterioration, only about 10% to 20% of the original materials could be reused in the restored vessel. It is common for wooden boat restorations to reuse 0% of the original wood, so even 10% is considered high. Ironically, the steering wheel on the restored Minnehaha originally came from the Hopkins–Minnetonka.

In the end, Minnehaha’s story is an exceptionally unique case that cannot be repeated. Her salvage was the result of a fundamental misassumption and would not have been allowed had the truth been known. From an engineering and logistical standpoint, her salvage was a remarkable operation in and of itself. Her restoration, miraculous in so many ways, is a huge testament to the enthusiasm, dedication, and tenacity of dozens of volunteers and the community at large. Having provided rides for an average of 10,000 passengers annually since 1996, the restored Minnehaha is a most uncommon success story. It comes as no surprise that she is an incredibly special part of Minnesota’s maritime heritage.

About 4 years ago a group of us who graduated from Minnetonka High School class of 1970 had a reunion and took a ride on the Minnehaha. I had no idea of this history. Great read! I have a picture of all of us standing at the upper deck railing.